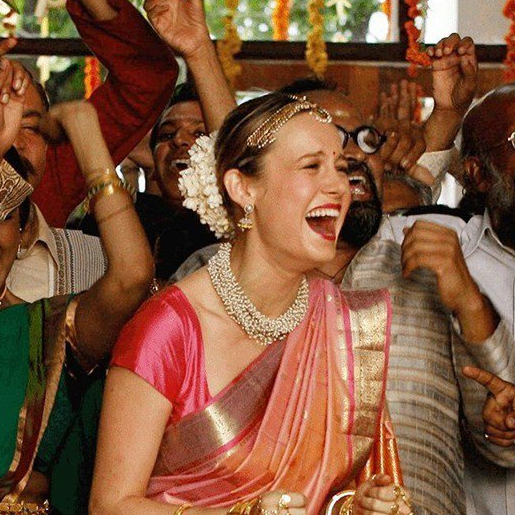

dir. Josh Boone

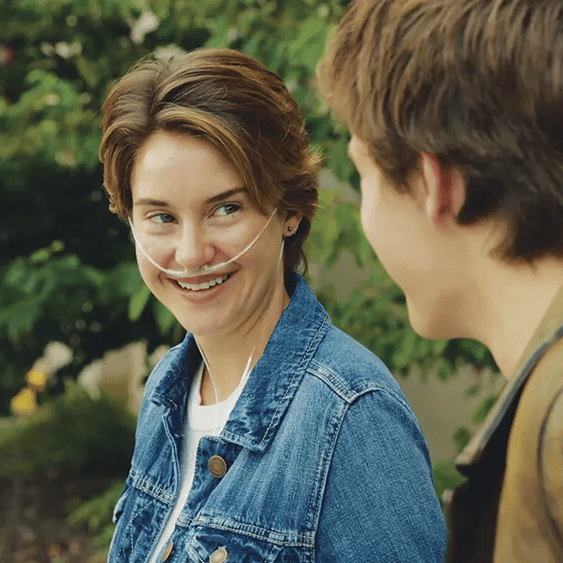

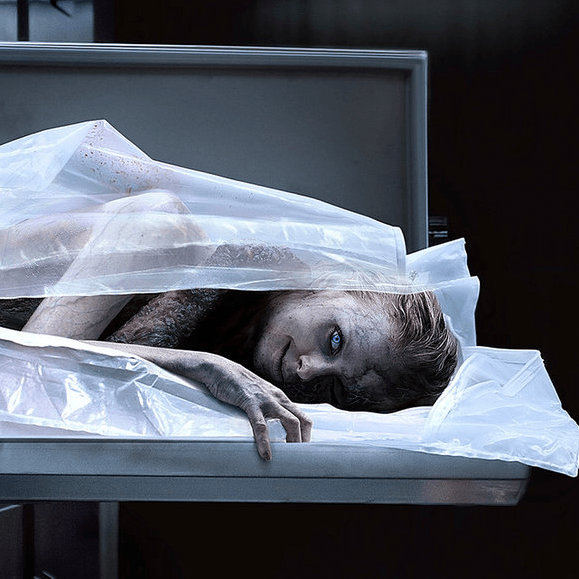

Based on the popular YA book by John Green, The Fault in Our Stars follows cancer patients Hazel (Shailene Woodley) and Gus (Ansel Elgort) as they navigate love, sickness, and death. One of the greatest hurdles is that Hazel and Gus are neither likeable nor compelling. They quote literature and hackneyed philosophy at each other a lot, but neither seems to have any genuine passions or interests. Their love story seems to be based on proximity and shared experience of illness, little else. The story also takes a very strange turn when the duo venture to Amsterdam at the invitation of an author they love; when they are rebuffed they wind up on a trip to the Anne Frank museum, and being applauded by strangers as they make out in the middle of an exhibit. As if that weren’t horrifying enough, we’re also forced to sit through the incel-adjacent rages of their friend Isaac (Nat Wolff), and watch the three band together to hurl eggs at the house of a poor innocent girl whose only crime was to break up with him. But no one calls them out, because they have cancer. The moral of the story seems to be that sick people can do anything they want without consequence, including keeping important and devastating secrets from their significant other, because they’re sick. Faults in character, faults in story, faults in message – if only it stopped at The Fault in Our Stars.